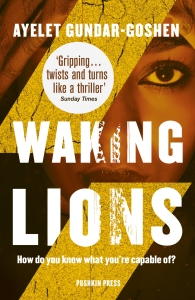

Interview with Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, author of ‘Waking Lions’

Thriller Books Journal is pleased to host Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, author of ‘Waking Lions’, a daring, genre-defying novel that cleverly blends a gripping noir story set in contemporary Israel with subtle insights on how our minds work when faced with life-or-death choices.

Thriller Books Journal is pleased to host Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, author of ‘Waking Lions’, a daring, genre-defying novel that cleverly blends a gripping noir story set in contemporary Israel with subtle insights on how our minds work when faced with life-or-death choices.

[Q]: Hello Ayelet, nice to meet you and thank you for joining us. Let’s start with some background: was writing fiction your first professional calling, and if not, how and when did you start writing?

[A]: I did my MA in clinical psychology, and I consider it as my “profession”. During my BA and MA studies I also worked for the Israeli civil rights movement, and as a news editor on a big newspaper. Actually, it took me a long time to get over the fear of being pathetic and to start writing my first novel. Deciding to write a novel isn’t much different from deciding to ride a dragon. Scary.

[Q]: ‘Waking Lions’ is a novel with many layers of meaning, one that straddles genres effortlessly. So I’ll start by asking you what drove you to write it, which character or idea was the spark that ignited the story for you.

[A]: I was twenty when I met the protagonist of this novel. I was travelling in India and met a young Israeli who just sat in the guesthouse and stared for nights. He had a dreamy face and long, light colored hair. He was just out of military service and supposed to be having the adventure of his life. But there was something wrong with him. The guy looked frozen. He didn’t speak, he didn’t smoke, he didn’t do anything. He just lay on the hammock in the guesthouse and stared at the sky. Something was eating him up inside, that was clear.

Eventually I went to him and asked if he was alright. He told me that several days ago he had hit an Indian man with his motorcycle, and had fled.

I was haunted by this story for ten years before I sat down to write it. I wanted the readers to finish the book with this question: had it happened to you – driving home to your family late at night, hitting an un-named refugee, one that looks like 1000 other people, like the cleaner in the supermarket, and no one would ever know – are you absolutely sure you wouldn’t flee? The guy I met in India didn’t look like a bad guy. And I think had he hit a young Israeli girl he would have taken her to a hospital. But he didn’t hit an Israeli girl, he hit someone that looked different from him, and I believe that’s the difference.

[Q]: One night one of the novel’s main characters, Dr Eitan Green, a neurosurgeon who’s happily married to Liat, a police inspector, accidentally runs over an illegal Eritrean immigrant. He then makes the ‘wrong’ choice: he drives away, leaving the man to die. Yet Eitan is a sensitive family man and a dedicated professional. Are we defined more by our choices than by our personality? Eitan has had to make tough choices in the past, so can blind chance and random impulse alone be the basis of our behaviour?

[A]: That’s one of the things that bothered me while writing the novel. The arithmetic of “how much good is equal to one big bad”. I’m not sure I have an answer yet. I like the existential point of view in which a person is the sum of his choices – nothing more, nothing less.

What defines Eitan more – a life of careful driving, of medical studies, of helping old ladies with their groceries– or that single moment of the hit-and-run? Forty-one years of life versus a single moment; and even then, perhaps that moment represents a great deal more than its sixty seconds, just as one bit of DNA embodied the entire human species.

[Q]: The novel’s twin central character alongside Eitan Green is Sirkit, an immigrant woman from Eritrea, whose husband Asum is accidentally run over by Dr Green. She is an illegal alien, scraping a living by cleaning floors in a restaurant and sharing a stark, virtually hopeless life with dozens other migrants. Yet, after Asum’s death, she shows a strength of character and a clarity of purpose that are truly extraordinary. Can you tell us more about Sirkit’s genesis as a character, and about what she means for you?

[A]: As I said, I was haunted by this story for ten years before I sat down to write it, and one of the reasons was that I couldn’t find the right path for the protagonist. I didn’t want to write a 300 page-novel about a white guy feeling guilty and contemplating it alone in his decorated living room. Only after I realized that this person is blackmailed by the widow of the refugee he killed did I sit down to write. Sirkit was the key to the story.

Sirkit’s life changes because she is the only witness of the hit-and-run. The traditional female role – watch, and be quiet – is now ironically charged. Because what she sees when she witnesses the accident gives her power over this man. The roles are switched.

It was very important for me that Sirkit wasn’t this “black angel”, a saint, an African Maria. I wanted her to be a real human being, with dreams and desires and aspirations for power. I think to portray her as a saint is just as dehumanising as portraying her as an ultimate evil. A “refugee” is no more of a saint than a “middle-class man”. Both are labels, and behind those labels there are real people – who love, cheat, hate and trust.

[Q]: Besides Eitan Green, Liat and Sirkit, ‘Waking Lions’ is built around an incredibly varied cast of characters: there are Sirkit’s fellow-migrants, mostly nameless but no less significant; Ali and Mona, two Bedouin youngsters who become tragically embroiled in the aftermath of Asum’s death; Guy Davidson, a kibbutz owner with a dark secret. Together they paint a picture of an Israeli society that seems to struggle to integrate all of these different elements. Is this true, and if so, which challenges do you think are the toughest to tackle?

[A]: I believe it’s the writer’s job to force the reader to look where they usually avoid looking. Literature is an act of seeing, different from the everyday gaze. The refugees and the bedouins are the unseen people in Israeli society, and I wanted to write about that which is unseen.

[Q]: One of the features I most enjoyed in ‘Waking Lions’ is how it doesn’t shirk from showing the characters’ weaknesses, in fact how in some cases it makes those weaknesses the characters’ defining features. How hard is it for an author to be honest about a character, to make him or her a fully realised individual and not simply an opportune prop to the plot?

[A]: A plot is interesting only if it happens to people, real flesh and blood people. Otherwise, why should I care if the doctor is blackmailed, or if he goes to prison? In order to really care about my characters I have to make them as real as possible, like imaginary friends. And the moment you know what it is that your character is most ashamed of – what’s her weakness is – that’s when you know she’s a human being.

TBJ: Thank you very much for your time Ayelet, and we look forward to reading more of your work soon!

Picture credit: Nir Kafri