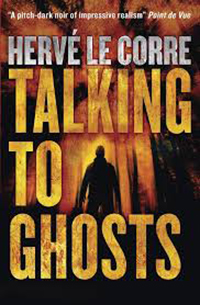

Talking to Ghosts – Hervé Le Corre

This is an ambitious novel, as dark, bloody and harrowing as classic French noirs can get.

This is an ambitious novel, as dark, bloody and harrowing as classic French noirs can get.

I enjoyed ‘Talking to Ghosts’ on several levels, beginning with Hervé Le Corre’s daring in trying to add new twists to the traditional police procedural mix, without losing focus and still keeping the narrative pace up.

This is his eighth novel and the first to be published in the UK, in Frank Wynne’s excellent, atmospheric translation. Le Corre was awarded the Grand Prix du roman noir français de Paris for his fifth effort, L’Homme aux lèvres de saphirin (2004), while ‘Talking to Ghosts’ won the Prix Mystère de la critique in 2010.

Right from the start Le Corre plunges the reader into pain, both physical and psychological. And for once the pain is shared between victims and detectives. Commandant (equivalent to DCI) Vilar, who’s investigating the brutal murder of a part-time prostitute – her teenage son Victor found the dead body in the bedroom and lay alongside her for 2 days– has had his 8 year old son Pablo kidnapped five years before, presumably by a paedophile. Pablo was never found, alive or dead, and his tragic absence is Vilar’s daily dose of mind-numbing pain.

The story develops along three parallel strands, which Le Corre juggles with skill: while Vilar and his partner Pradeau, himself nursing a rather wrecked family life, investigate the murder of Victor’s mother, Vilar is being stalked by a psychopath who, after claiming he has found Pablo, has tortured and killed a retired colleague who was helping the commandant in the search for his missing son. And at the same time, Le Corre gives us something of a coming-of-age story, just as dark and painful as the crime fiction one he’s spinning, as we follow the distressing path of Victor, from child centre to foster home, from terrified, helpless orphan to hardening youth.

Le Corre shows a high degree of self-assurance in handling this complex material. It takes a few chapters for his web to fully envelope the reader, but once caught, I was swept along by the stream of his narrative, as majestic and relentless as the Garonne river that flows through Bordeaux – where Vilar lives and works – and pours via a huge estuary into the Atlantic. Le Corre’s sculpted prose is painstaking in bringing out the intense psychological overtones of his characters’ stories, and mesmerising in depicting the elemental intensity of his locales, both the town of Bordeaux and its surroundings, where acres of vineyards blend into dark, brooding waters and mud-caked shores.

The bereaved detective is not uncommon in contemporary French crime fiction, I think of Pierre Lemaitre’s Commandant Verhoeven, but is less so in Anglo-Saxon or Nordic novels. Even a warped character such as Jo Nesbo’s Harry Hole has never been through the mental torture Vilar has been subjected to by the criminal he is chasing. For Vilar does give chase, with the crazed persistence of a man possessed. Such intensity and hurt is difficult to pull off, requiring author and reader to be constantly soaked in pain and suffering, within and without the savage brutality of criminal investigations. Full credit to Le Corre for having the audacity, the narrative skill and the plotting savvy to weave a tapestry worthy of the best noir tradition. We’re not in Paris, we’re far away from chic, picture-postcard France, but this, Le Corre starkly reminds us, is what life is about. And death too.

Sounds like a very good read!

H. Le Corre is a very powerful author, hope they publish some of his earlier novels too

I found ‘Talking to Ghosts’ excellent crime reading, tough and punchy. Commandant Vilar is a memorable character, well done H. Le Corre.